Helen Pyne ’11 Brings YA Literature to Impoverished Girls at Daraja Academy in Kenya

Daraja student

Every girl has the right to learn; gender should not determine opportunity.

That’s the belief behind the founding of Daraja Academy, a secondary boarding school in Kenya for impoverished but exceptional girls. For families living in deep poverty, access to education is already limited, but in developing countries like Kenya, sons are still far more likely to attend secondary school than daughters. And without a high school education, girls are often condemned to early marriages and pregnancies and are unlikely to get jobs that enable economic self-sufficiency. Education is the fastest bridge out of poverty, but too many girls have no hope of crossing it.

Daraja means “bridge” in Swahili.

The school, founded in 2009 by two Bay Area educators, Jason and Jenni Doherty, provides shelter, food, healthcare, uniforms, counseling and everything needed for an education to the 120 students who live year-round on campus. Located in Nanyuki, a town about 3 hours north of Nairobi by car, Daraja is ranked in the top 10% of private secondary schools in the country.

All accepted students are given scholarships, so the girls pay no tuition but commit to volunteering 30 hours of community service for every year they spend at Daraja. Thanks to the innovative, four-year W.I.S.H. (Women of Integrity, Strength and Hope) curriculum, which teaches sex education, public speaking, human rights, and peace building, the girls are empowered to see themselves as leaders and agents of change in the world. They learn valuable lessons about tolerance as well, since 34 of Kenya’s 43 tribes, or ethnic communities, are currently represented on campus. When a girl from the Samburu tribe is assigned to sleep in a bed next to a girl from the Pokot tribe, with whom they’ve been fighting over cattle and land rights for hundreds of years, it’s a light bulb moment when the girls realize they’re more alike than they are different.

Three Daraja students Helen and her husband have sponsored.

Welcome, Helen, and thank you for sharing your experience with the Wild Things readers. How did you get involved with Daraja Academy?

Nine years ago, my husband and I were introduced to the school by a friend. Intrigued, we decided to sponsor a student and have continued to do so every year since. After joining the board in 2017, I realized I had to visit the campus. This summer my dream came true when we traveled to Kenya and spent a long weekend at Daraja, teaching workshops to the students. I taught creative writing and journalism; my husband taught public speaking and assertiveness training. We brought a duffle bag full of books by young adult writers, many of them written by VCFA alumni and staff.

It was the Daraja students’ personal stories, however, that inspired and moved me most. Just like the fictional protagonists we work so hard to create, the courage, resilience and resourcefulness of the students I met, and their heroic efforts to overcome crushing obstacles in order to get an education, captivated me. I’m already planning my return, only next time I will stay on campus for a week or two and teach a series of writing workshops.

Once a year, the admissions team travels around Kenya, interviewing girls for the next freshman class. There are approximately 300 applications for every new class of 30 spots. I am told that the stories shared during the interview process can break your heart.

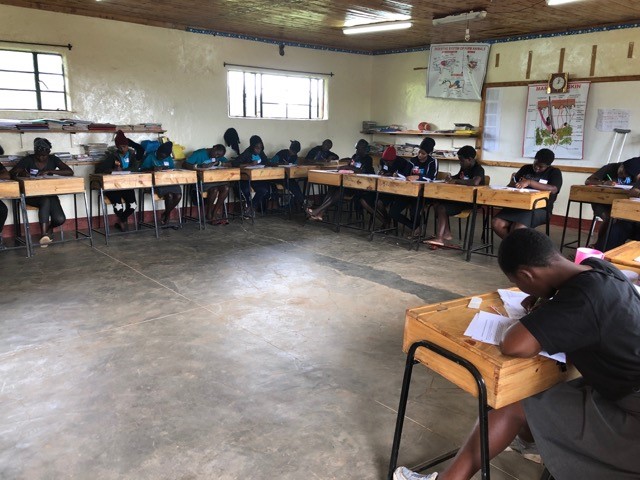

Helen’s creative writing classroom.

One girl, for example, told the interview team about how she walked eight kilometers to school through a forest, where she was in danger of being attacked by armed men. She didn’t have food at home, and often only ate when teachers brought her food for lunch. She studied during breaks because there was no light for homework at home. To avoid a marriage that her father had planned for her, she had to flee across the country—at the age of fourteen.

Alice’s story (not her real name) is even more chilling. Alice, a child bride, escaped on the night of her wedding and eventually made her way to Daraja. Alice was told at age 15 that she was to be married. She had already been forced as a young teen to undergo the ritual of female genital mutilation (FGM). Alice resisted getting married, but even her mother couldn’t find a way to stop it. So, Alice was indeed married, but on the night of her wedding, she ran away. In town, she looked for students in uniforms, and asked them for directions to their school. She described her story to the head teacher, who took her in, providing housing, a uniform, and books. Yet, he couldn’t offer her any more support, and she started working in the evenings to earn money by doing things like washing clothes. Alice made efforts to send money home to her mother and siblings.

The family Alice lived with didn’t provide her with water to drink or use for bathing. So, Alice found a five-liter jug and used it to bring her own water home from school. When the family left her alone without electricity or food, she borrowed a torch (flashlight) from the neighbors, and kept on studying. Despite not having food or electricity during the week of her exams, she completed her 8th grade exams, required for acceptance in high school, and was accepted at Daraja.

“When impoverished families can only afford to educate one child, they usually choose their (1) sons over their daughters. In 2013, (2) 23 million secondary-aged girls worldwide weren’t in school. To this day, women account for (3) 2/3 of the world’s illiterate. This has unsurprisingly correlated to the fact that women still constitute the vast majority of the world’s (4) 1.3 billion people who are living in poverty.

In Kenya, only 48% of girls are enrolled in (5) secondary education, and 16% of women in Kenya are (6) functionally illiterate.”

1) https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/educating-girls-is-the-key-to-ending-poverty/

2) https://www.unicef.org/education/bege_70640.html

4) http://www.un.org/womenwatch/directory/women_and_poverty_3001.htm

5) http://www.unesco.org/eri/cp/factsheets_ed/KE_EDFactSheet.pdf

6) http://www.unesco.org/eri/cp/factsheets_ed/KE_EDFactSheet.pdf

One of Helen’s classes of students at Daraja.

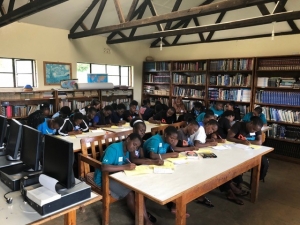

Daraja students working on their writing.

What’s a typical school day like for Daraja students?

The girls rise around 5:00 am. They make their beds and clean the dormitory before carrying out other campus chores (fetching water for the kitchen to wash dishes, carrying in the filtered drinking water, sweeping walkways, mopping classroom floors, wiping tables, etc.,) all before they start their school day! After classes end for the day, students have a sports period in the afternoon, followed by dinner and chores, then study hall every night from 7:00-10:00 pm. There’s also a farm on campus where the school gets most of the vegetables they serve (when in season), and students help out in the gardens there too.

What does it mean to the young women to have access to YA books?

The students were thrilled to receive the books, but I didn’t stay on campus long enough to hear what they thought after reading them. (I will find out though!) Daraja is situated on a site that was previously used for a boys’ education program, so the small library that the school inherited definitely needed updating with more books written for teenage girls.

Because Daraja students come from cultures very different from ours, I included a lot of fantasy novels. I figured those imaginary worlds might have more universal appeal and the situations in which characters find themselves might be more relatable than in some contemporary novels set in American high schools. Most of the Daraja girls are not as sophisticated as their American counterparts. A number of them, for instance, had never used a computer before coming to Daraja.

I kept diversity and inclusion in mind when choosing titles, making sure that I selected books with protagonists of different races and religions. I included a good number of books written by authors of color—especially African American authors. I talked to librarians and the teen book buyer at my favorite local bookstore, who hooked me up with books like Tomi Adeyemi’s Children of Blood and Bone. Katie Bayerl gave me some terrific recommendations, and Cynthia Leitich Smith’s website was invaluable. Daraja has quite a few Muslim students, so I made sure to include novels with Muslim main characters as well.

Kenyan society is very conservative, so unfortunately LGBTQ people face severe discrimination and intolerance. Being gay is not openly talked about; in fact, it can be downright dangerous to reveal. Knowing that, I thought it was important to bring books not only about girls and boys falling in love, but about boys falling in love with boys and girls falling in love with girls. I have no idea yet how these novels will be received. The stories may shock some of the students, but they may also reassure them.

Mostly, I believe that given the atmosphere of openness, acceptance and tolerance at Daraja that these girls will be better equipped after reading them to go out into an infinitely more complex real world to be the change makers and ambassadors of peace we so desperately need. I like to think that these YA books will start discussions, get students thinking and act as a kind of bridge to help transport these amazing girls into their future lives where their skills and convictions can make a positive difference.

One of the girls I spoke with on campus was telling me how wonderful it was at Daraja because there was no bullying. Then, she commented, “But I’m sure kids in the United States don’t have to deal with that…” She was astonished when I told her the truth—that sadly, bullying was a huge problem for American teens as well. Exchanges like this were eye-opening for us both.

Students writing and playing!

How does the work you do at Daraja affect your writing life as a whole?

For writers, everything we do is grist for the mill—relationships, jobs, interests and activities. But travel experiences are particularly valuable because, just like a good book, they can change your perspective. Witnessing the hardships that Daraja students have endured and overcome to get the education they dreamed of is inspirational. I’m in awe of their resilience. Now I’m less likely to complain when I receive another rejection letter or have to revise my novel again for the umpteenth time. My stay at the school helped me to see with new eyes, and that is a gift I will take back to my fiction writing. I’d love to write a story from the perspective of a Daraja student someday, but for now my goal is to help the girls write their own stories and share them with the world.

Please contact me for more information on my experience at this amazing place. This school relies on donations, so please consider donating if you are able!