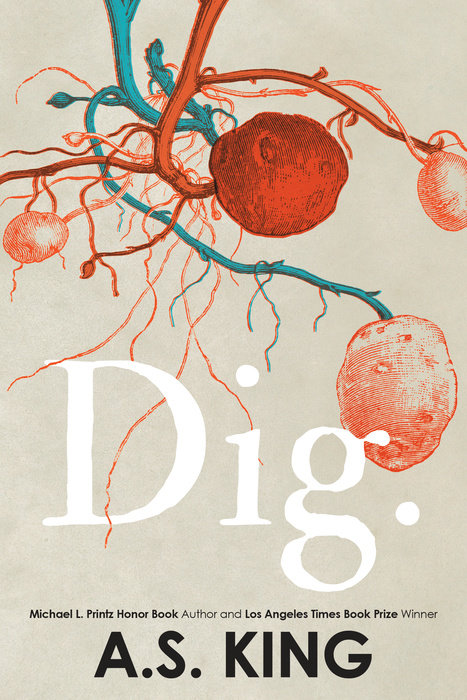

DIG. by Faculty A.S. King

Today we are celebrating the release of WCYA faculty A.S. King’s latest young adult novel, Dig.

The Shoveler, the Freak, CanIHelpYou?, Loretta the Flea-Circus Ring Mistress, and First-Class Malcolm. These are the five teenagers lost in the Hemmings family’s maze of tangled secrets. Only a generation removed from being Pennsylvania potato farmers, Gottfried and Marla Hemmings managed to trade digging spuds for developing subdivisions and now sit atop a seven-figure bank account – wealth they’ve declined to pass on to their adult children or their teenage grandchildren. “Because we want them to thrive,” Marla always says.

What does thriving look like? Like carrying a snow shovel everywhere. Like selling pot at the Arby’s drive-thru window. Like a first class ticket to Jamaica between cancer treatments. Like a flea-circus in a double-wide. Like the GPS coordinates to a mound of dirt in a New Jersey forest.

As the rot just beneath the surface of the Hemmings’ precious suburban respectability begins to spread, the far-flung grandchildren gradually find their ways back to one another, just in time to uncover the terrible cost of maintaining the family name.

Dig. is available now from Dutton. We asked Amy some questions about Dig., her writing process, and teaching at VCFA in the Writing for Children & Young Adults program.

Thank you for joining us, Amy!

What was the initial spark that inspired this book?

I knew for a long time that I wanted to write about whiteness. That sounds like a strange place to start, but that’s what I knew at first. I’ve had a lifelong fascination with race, hate, and what it means to be white in America. I grew up in rural Pennsylvania and know plenty about extremist racist groups, but I wanted to dig deeper, more off-limits soil. I wanted to find out what made American white people so tragically unwilling to change their perspective about polite, middle-class, everyday racism.

You’ve been working on this book for quite a while. What were some of the biggest changes from early drafts to publication?

I started writing the book about four years ago—a scene of a young man shoveling snow late into the night. That young man became our Shoveler, the first of five teen characters you meet when reading the book. I kept writing him, alongside a character named The Freak who showed up out of the blue, but neither would really tell me what they wanted or what they wanted me to do with them. I got to page 80 or so after a few months, and I got really frustrated. This is so boring. None of these characters are telling me anything, I’m done. I put the Shoveler and The Freak away and figured I’d write another book. So I started writing about a young woman named CanIHelpYou?, who works at Arby’s and might sell drugs on the side, and then, as a scene unfolded in her nearby park, who arrived but the Shoveler, with his snow shovel, but with no snow in sight. And I thought: Oh. Okay. That’s an A.S. King novel.

I dug the pages of the Shoveler and The Freak out of storage. I figured out how they fit together with CanIHelpYou? And Loretta the Ring Mistress. Malcolm showed up. It took me more than a year to figure out what was really going on.

Fact: I didn’t really know what was truly going on until around page 350, about 2.5 years in. The Freak told me her secrets. I had to go back and make sure the writing fit the secrets. It turned out, it pretty much did. As if my unconscious brain had already pieced the puzzle, but hadn’t notified my conscious brain about it. (Thanks, brain.)

So the long answer to your question is: like any book, this one has undergone a lot of changes as described above. The short answer is: Actually, miraculously, not as many changes as you’d think.

I reckon that’s because I was able to take my time writing it.

In many of your YA novels, you include the perspectives of adult characters as well as teens. Dig. shows us the thoughts of this family’s grandparents and grandchildren, but keeps the middle generation at a distance. How did you choose which voices to include?

Marla and Gottfried came to me first—back when I’d written the opening of the Shoveler and The Freak. So did Bill & Jake Marks. Those two short first chapters came very very first—the same as they are now in the finished novel. So, Marla and Gottfried were destined to be the vehicle for this story from the first day I wrote.

Describing the process or the decision-making is almost impossible because I follow the characters, not the other way around. I know that sounds like my brain is made of artsy homemade granola, but it’s true, so I can’t really tell you how I choose. It seemed important to skip Generation X. It’s symbolic, maybe, that I decided not to hear from them, considering that’s been Gen X’s experience and a pretty common joke for people of my generation. So, in hindsight, I’ll say that I meant to do that. (But I didn’t really mean to do that.)

Most of your books are categorized as young adult, but you have published one middle grade book and have another on the way in October. What are some differences in how you approach writing for these distinct audiences?

I’m so glad you asked me this. Because I have no idea. Allow me to brainstorm out loud.

First, I guess I have to say that I’m still not sure if I’m any good at middle grade writing. I have heard compliments, and that’s great, but me in my office, am I good at writing MG fiction? I find it hard. It’s far harder for me to write a middle grade story than a young adult or adult story.

Someone recently asked me if it was because I have to avoid curse words. (They clearly know me.) But it’s not. It’s the age group. They are a really hard group of people for me to relate to, I think. Or so I thought until I started writing this answer. Sitting next to me is my 11-year-old daughter. She is the most amazing human being. She is resilient and smart and sassy and going through the painful process of learning who she can trust and who she can’t in her schoolyard life. I can certainly relate to that, but I guess I can’t relate to the firsts that go with it.

Sorry. I didn’t answer your question. But it’s an easy answer: I don’t approach it any differently. I sit, I write, I listen for the story, and I am honest.

Speaking of listening – do you write in silence, or with music? If you put together a soundtrack for Dig., what are some artists or songs you would include?

I write first drafts in silence, but there is always music in my life while I’m writing. In the car, in the house, in my ears as I travel. During revision, I usually find a trance song for a character or a part of a book. Example: Kate Tempest’s “Ketamine for Breakfast” from her album Let Them Eat Chaos is CanIHelpYou?’s theme song. I listened to it non-stop on a loop while I revised her parts. Also: “Europe Is Lost” (listen to this!) and “Tunnel Vision.”

Let’s face it. Kate Tempest’s Let Them Eat Chaos is the theme album for this book. It’s a genius album and I highly recommend her, all of her work, everything she’s ever done, and anything she does in the future.

Then there’s Damian Marley’s Welcome to Jamrock and Stony Hill. And random tracks, like that one he did with Skrillex. A lot of Bob Marley and the Wailers.

Oh! And Beyoncé’s Lemonade.

Also: Panic! At the Disco and Twenty Øne Piløts.

I’m probably forgetting some. It was a long writing process.

But mostly Kate Tempest. Seriously. Listen to her work. Read her work. Google her poetry.

Dig. contains surrealist elements in your signature style, yet it has a distinctly different “feel” compared to your earlier work. Was there anything different about how you approached the surrealism in this book? How has your writing voice developed over time?

Approaching surrealism isn’t ever something I plan. But I can say that I feel a lot freer to be myself on the page now than I had for years, and myself is, quite clearly, a surrealist. I was with one publisher for five books, one per year, and my editor there loved weird stuff, but my brand of weirdness was not what they really wanted as a group—and everything there was done by the group, pretty much. Plus, with the yearly deadline, it’s not like I had time to explore myself or my subject matter beyond a year or two of research and writing.

So, with Dig., I had several years to write it. I mean, I had a deadline, yes. I was aiming for earlier, yes. But life got complicated and no pressure was put on me to complete the book any faster. There was no group breathing down my neck making me fear my publishing future. And so, the book got to grow at its own pace. And the surrealism had room to grow—even if I didn’t know that was happening.

I am always the last to know, pretty much, what the hell my characters are doing.

My voice has grown, then, with a mix of time, patience, acceptance, and hard work. Hard work because I work really hard. Time because writers should have as much time as they need to write the book they need to write. Patience because sometimes that amount of time feels too long and the cupboards are bare by the time you’re done. Acceptance because I had to accept that my unique brand of writing is allegedly “hard to market,” so no matter how long it takes, or how awesome I think it turned out, I will barely get to the next book without the bare cupboard problem again.

I should add that I haven’t just come to accept this last part. I kinda roll around in it. The irony that I write what I do (books about love, compassion, the human condition, and shrugged-off trauma) and that it’s ignored, pretty much, by the mainstream, well, it’s symbolic. Which makes my work and my life a metaphor and I EAT METAPHORS FOR BREAKFAST, AIDAN.

White privilege is a prominent theme in Dig. This story is a remarkable illustration of how white people consciously and unconsciously reinforce patterns of racist thinking over generations. This mindset is limiting – until we become aware of it. Do you have recommendations for readers who want to learn more about recognizing and interrupting this toxic cycle?

This is a great question. I’m not entirely sure how to approach it but I’ll start here: yes, white people are trapped in a cycle of white privilege and systemic racism same as men are trapped in a cycle of male privilege and systemic sexism…until something clicks and awareness arrives. It’s what we do when the awareness arrives that matters.

When I talk about feminism, I often talk about men and how we need them on board for women to one day have full human rights. They are in control, so they have to be the ones who make the change. Women can make some changes, sure—if they sit in positions of power…but what help does that do me, a woman who has to take her husband with her to the specialist’s office because otherwise her male hematologist won’t actually speak or listen to her?

I often talk about how the best way to engage men in the idea of feminism and help them see their privilege is through kindness, because shaming people rarely will change them. We are fragile beings, all of us. All of us. (All of us.) Kindness will almost always win support when shame will rarely do the same magic.

And so, two years ago, I started saying something during some of my school visits. I started to tell the white students in the room (in a very kind way) that they are, in fact, white, and I asked them to think about what that really means here, in the USA, right now. Discussions happened. Magic was made.

So, what would I suggest to white people who want to recognize and interrupt this cycle? Step one: notice that you are white and explore what that means. If you are out of high school, then you should be able to do this—because I’ve watched thousands of high school students do it without any issues.

If you’re way out of practice when it comes to changing your mind, I suggest reading Race to Incarcerate: A Graphic Retelling. The book makes very strong points about poverty and the imbalanced incarceration of African-Americans. These things are not coincidental, have been completely planned through many generations, and have yet to be challenged fully or dismantled. That’s a pretty bad description of such a powerful book, but trust me. Get a copy. Read it. You will suddenly realize that you believed a ton of racist propaganda in your life without ever knowing it. You will certainly realize that we live in a racist system that was set up centuries ago and that it will be nearly impossible to escape that system.

I think the first thing you have to do to interrupt this cycle is that you have to understand that if you are white and live in this racist system, that you are, in fact, part of the system, and that you are, in fact, no matter your economic situation, gaining from your whiteness. After that, it should be pretty easy to recognize that you live in a white supremacy. After that, then, it should be pretty easy to admit that you are, in fact, by default, a racist. If you are white and you were born on American soil and you’ve lived your life relatively free of fear, then you need to understand that’s because you are white and you live in a white supremacy. You live in a world made for you.

This is very hard for a lot of well-meaning white people to swallow. But look—this country was founded on the trauma of racism and got rich off that same trauma. Everything we have as white people starts with this history.

I know it’s hard to take.

No one likes being called a racist.

But come on. Be real with yourself. And your kids. And anyone who will listen. Racism is about power, and if the world you live in was made for you, then you’re the one with the power.

The sooner this becomes a reality that we can talk about, the sooner we can at least start making moves toward some sort of equity. Did you see all the weak words in that sentence? That’s because I am feeling kinda hopeless about it all. To paraphrase Dig.: The key to the kingdom was ours. Why would we not take it?

And indeed, why would we give that key of power away?

How could we do that in a culture that makes us feel constantly financially unsafe?

This is how they got us.

They got us with the money.

And our knuckles are white from gripping it so damn tight and keeping it safe from…those people who shouldn’t have it because we have made up a million reasons why, but we refuse to admit that most of those reasons are racist.

Sorry. I was supposed to be recommending things. There are many books out there to read. I quite enjoyed the very straightforward So You Want to Talk About Race? by Ijeoma Oluo, White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo, and A People’s History of the United States by Howard Zinn. Also: go buy all the Black History flash and trivia cards from Urban Intellectuals. I guarantee you will learn a lot through those cards. Mostly, I hope you will learn that your history lessons were ridiculous.

Also: go listen to the Uncivil podcast. That show is brilliant and the first season will show you just how twisted the history you learned was.

Short answer: Educate yourself about the reality of American history. Pass that education onto the youth in place of the awkward silence that’s been there for generations.

It struck me that so many of the problems these characters are facing stem from their difficulty expressing love in a way that is comprehensible. How can we learn to push past restrictive assumptions of what is “respectable” and truly connect with our loved ones?

THIS IS THE MILLION DOLLAR QUESTION. Thank you for asking it. On the surface, beyond white privilege and supremacy, the larger themes in the book may seem like money or generational differences or flea circuses or potatoes or the invention of the flush toilet. But really, it’s about love. Most of my books are.

How to love people depends on the people, I guess. But the biggest tripwire I see is people who are damaged by lifetimes of judgment. Self-judgment, judgment toward others, and judgments that they battle from the outside. We are so quick to judge what people do and how their lives unfold that humans have become a sort of knee-jerk people police. It’s hard to love when you are so busy thinking about what other people should be doing. It’s hard to love when you’re thinking about why you’re better than other people. How can you take care of anyone when you’re so unforgiving? How can you learn? How can you grow?

So, in a word: humility. It is impossible to connect truly with other human beings without humility. And considering humility, what are the “respectable norms,” then? For me, respectable norms in a family are support, unconditional love, and feeling happy when a family member achieves something cool. Random hugs. Random phone calls to say I love you. All of that—it’s plenty respectable. This uptight white, quiet family life we’ve been cultivating is dangerous. Leads to jealousy among family members, restrictions on personalities, and, well, judgments. And here we are again, back at judgments.

Let me try again, to see if it always circles back. You mention that the characters in Dig. are dealing with “difficulty expressing love.” Where do you think that comes from? And what do you think it causes?

I think difficulty expressing love and affection comes from a bunch of places—from dysfunctional families and a culture obsessed with money, stuff, perfect bodies, and fame—and the result is a giant ball of loneliness. I believe loneliness can cause a kind of self-centered myopia, especially if the lonely person is angry about their loneliness. (See also: incels and other people who like to blame their unhappiness on others.) I am no stranger to people who have difficulty expressing love, and I am also no stranger to entitled lonely people who rarely look within and instead, point outward in blame. Which is technically judgment. And so, we land here again. I guess I think we humans have a judgment problem. As someone who sifts through the human condition for a living, this is where I have ended up. Judgments are the opposite of love.

To connect this to your last question: how do you ever get people like this to recognize that they are default racists? These are defensive winners. They can never be wrong. They are the epitome of white and the opposite of humble. How will you help them love, then? You can’t. Toxicity is in the veins. Just like trauma is in the soil of this country. The only way out that I can see is a compassion that many of us can’t seem to locate.

Shifting gears a bit now: You’ve been reading from the work in progress at recent VCFA residencies. How does the VCFA community affect your writing life?

I think I read from Dig. at VCFA three times now, and it’s always a buzz reading new, weird work to the VCFA community. I remember back when I read from I Crawl Through It for the first time during an Annual Mini Residency—Rita Williams-Garcia walked up to me right after and grabbed my forearm so tight and said the nicest things about what I’d read. The same sort of thing happened with Dig.

Faculty and student support really help me work through my own feelings of doubt and fear with an unfinished piece.

As for the wider way to answer this question: the VCFA community is a huge reminder of what I’m supposed to be doing with my life. Each residency is a sort of camp. Let’s call it Camp Light-a-Fire-Under-My-Ass. It’s inspiring to be around so many people with so many ideas and so much light and love. I have heard often on campus sentiments like: VCFA is more a family to me than my own family. None of us who feel this way mean any offense to our own families—it’s just that VCFA is a place of safety and support that makes us feel accepted. And I feel that, too. And so, the VCFA community has a huge, positive effect on my writing life. And my life in general.

Can you tell us about a favorite VCFA memory?

This is kinda impossible—who can pick just one? That moment when Rita grabbed my arm—I will never forget what she said and how that affected me / the day after Nova saw that ghost and she told us about it / That time it took me and Martine about 45 minutes to walk from College Hall to Noble in the ice, clutching each other the entire time / that event in San Francisco when about 20 VCFA alumni showed up—what? I couldn’t believe it. Seriously, Aidan, how am I supposed to answer this?

And while this may seem like a weird place to put this part of my answer, I need to say this somewhere. The outpouring of support I and my family received from VCFA students, faculty, and alumni when our daughter died last year was probably the most heartwarming, real, true, classy, touching, helpful, gorgeous, familial outpouring of love I ever experienced in my life. My VCFA family showed me what matters in life really quickly. I always told my kids that people will lie and judge and cheat in life, but it won’t make them happy. I can truly say that VCFA—if we ran the world, it would be a really epically happy place. Thank you to all of you who have reached out—and to those who sent quiet love, too. It meant so much more than you could ever know. That outpouring will stand as an ongoing and truly meaningful VCFA memory for me for the rest of my life.

What advice would you give a prospective VCFA student?

When you come to VCFA, drop your walls and get ready to dig deep into yourself. Please, be willing to experiment and play. Please know that you are in a safe place where people care about you and your writing and your success and your heart. Feel free to open it.

Now that all that sweet hippy stuff is done, I should mention that you need to be prepared to work your butt off. Work harder than you ever thought you could. Be prepared to get challenged by the best WCYA faculty out there. Be ready to cry and get frustrated sometimes. And be ready to improve. Because that’s the point. To improve. For all of us. As readers, as writers, and as human beings. I can’t think of a better place to do that than VCFA.

Also: for winter residency, buy Yaktrax.

Amy, thank you so much for sharing your thoughts with us. I can’t wait for more people to read and love Dig. as much as I did!

Thank you so much for these great questions and for having me on the blog today. I’m so glad you enjoyed Dig., and I hope to see some VCFA people as I make a short trip around the US this spring—Phoenix area, NYC, Philly area, DC, and Athens, GA—come see me! Free hugs and no judgments. Details on my website: www.as-king.com

A.S. King is the award-winning author of acclaimed young adult books including 2016’s New York Times Notable Children’s Book, Still Life with Tornado, I Crawl Through It, Walden Award winning Glory O’Brien’s History of the Future, 2013’s Reality Boy, the 2012 Los Angeles Times Book Prize winner Ask the Passengers, Everybody Sees the Ants, 2011 Michael L. Printz Honor Book Please Ignore Vera Dietz and a Middle Grade novel, Me and Marvin Gardens.

King has been called “One of the best Y.A. writers working today” by The New York Times Book Review. Twice a NTYBR Editors’ Choice, and many times landing on the best lists of Kirkus Reviews, Publishers Weekly, School Library Journal, as well as many American Library Association lists, King has managed to bridge a gap between teen and adult readers with her crossover approach to writing young adult novels. She has been an Edgar Allen Poe Award nominee, a Nebula nominee, a Lambda Literary Award nominee, and a YALSA top ten and BFYA pick. King’s short fiction for adults has been widely published and nominated for Best New American Voices.

After fifteen years living self-sufficiently and teaching literacy to adults in Ireland, she now lives in Pennsylvania.