Cloud Residency: An Inside Look at Online Learning

Residency is coming up soon, and for those unsure about making the trip to campus to attend a physical residency, Cloud residency is an alternative growing in popularity. Today, we hear from former Cloud GA and Coordinator, Anne-Marie Strohman about why Cloud residency is an option just as viable as in-person residency.

-

Tell us a little about what makes Cloud a viable, enriching option equal to the in-person residency.

AM: We’ve worked hard to integrate Cloud and Campus wherever possible, ensuring that all students have access to all faculty, relationships can grow between Campus and Cloud students, and the celebration, encouragement, and engagement among the community stays rich and connected. That said, Cloud is a very special place of its own. So much of the benefits of learning happen outside of workshops and lectures, and we foster those places with morning coffee, after-lecture discussions, lunches with faculty, and a dedicated Discord channel.

-

What are some benefits to the Cloud residency format and how have you seen students make these benefits work for them?

AM: I first served as a Graduate Assistant for Cloud, expecting to leverage that into a Campus GA position. But I loved the Cloud experience so much, I went on to serve as Cloud Coordinator for two residencies! I loved being in my own space, sleeping in my own bed, and seeing my family. I could stand up and walk around or stretch while listening to lectures. If you can’t attend a lecture, it’s available on our online platform quite soon after the lecture. One student this summer said they watched more lectures on Cloud than they ever had at a Campus residency, including lectures people recommended from the WCYA archives.

Some of the best parts of Cloud are the opportunities we provide for informal connection to other students, faculty, and graduate assistants.

- Morning Coffee is a space for students to ask questions, talk about writing, and get advice from each other.

- Post-lecture discussions, typically led by faculty members, allow for reflection immediately after the lecture and often include great craft tips and book recommendations.

- Each lunchtime, a faculty member or graduate assistant hosts Cafe Anna lunch, each one focused on a different topic.

These events, while more formal than running into a faculty member in the hallway or chatting with friends after a lecture, give some of the feel of those informal moments.

-

How do the Cloud GAs and Cloud faculty keep the magic and academic rigor we expect from a VCFA residency?

AM: Translating the academic rigor from in-person to online is the easy part. Workshops and lectures contain the same rich, high-quality content. Smart people are as smart online as they are in person.

The harder part is building community and creating trust in an online environment, and making sure everyone knows what time things start and which Zoom link to click on!

Each night, as Cloud Coordinator, I sent out an email highlighting upcoming events and deadlines, as well as detailing the schedule for the following day. We kept online schedules updated with accurate Zoom links. I worked with GAs to provide individualized accommodations and support to students who needed it. We also want to keep the fun happening! From GA readings to Poetry Off the Page, from supporting the student-led Juvenilia to planning the Cloud Social, GAs are actively providing spaces for students to come together as a community. One of the downsides of Cloud is that spontaneous fun is harder to come by, so we intentionally build in events that provide ways to connect outside of the academic schedule.

-

What were some ways you’ve seen students be pleasantly surprised with Cloud?

AM: I know some introverted students who find that they are better able to engage in the events they go to because they have true downtime in between. Some students who switched from Campus to Cloud were worried it wouldn’t be as rich an experience, but they ended up liking it better than they expected–they felt connected to faculty and other students, were able to watch more lectures, and were able to manage the intensity of residency more easily. For some, just being around their pets made for a calmer, more engaged residency. I’ve also seen students who were afraid of technology take the risk and really enjoy it. The GA staff was able to offer tech support before and during residency that made it possible for students to come into residency with less tech anxiety and then grow to manage the technology on their own. It wasn’t the distraction they expected it to be.

-

What are some challenges, expected or unexpected, that came with building an effective Cloud residency?

AM: Writers sometimes describe their writing process as “planning” or “pantsing” (writing by the seat of your pants). My motto is: “You can’t pants Cloud.” Planning ahead, communicating effectively, and having back-up plans for when things go awry are essential. I’ve worked in online education for a while, so I expected that community building would be the hard part. I feel like we’ve made great strides. I’m still constantly talking with people and thinking about how to make it easier to connect with others in the Cloud (and not only in ways that are easier for extroverts). Technology always brings new and unexpected surprises. While we’ve pretty much figured out the Zoom part of it, connecting with Campus for hybrid events can sometimes be a challenge. We’ve learned a lot over the past hybrid residencies, and now we test the tech in every room well before events start. That doesn’t mean everything works perfectly, but we’ve established effective communication between Campus and Cloud to handle problems when they inevitably arise.

-

What are some of the highlights of Cloud residency for you?

AM: I love that we now have true hybrid events–a graduate reading may have a Cloud faculty member introducing a Campus grad reader, or vice versa; two faculty members gave a lecture together, one on Campus, one on Cloud; graduation includes all the graduates as well as faculty from Campus and Cloud. In January, we happened to have our visiting writers and visiting editor speak from Cloud. Cynthia Leitich Smith and Brian Lee Young stayed for the post-lecture discussion and answered questions from Cloud students and faculty. Editor Nick Thomas came to a Cafe Anna lunch, in conversation with Campus faculty member Evan Griffth (who joined us on Cloud) to talk about the publishing industry in an informal setting. And always, the student-led Juvenilia, where those who attend bring writing from any stage of their childhood to share. On Cloud, people can share childhood photos and images of their work. And Children’s Book Jeopardy at the Cloud Social is the best.

-

What would you say to people who might be considering Cloud residency?

AM: Try it! Cloud is a really special place. It’s a robust experience where you’re steeped in craft knowledge, develop relationships with faculty and fellow students, and can also be in your own space.

-

What advice do you have for first-time Cloud students?

AM: First, as many of us found working from home during the pandemic, it can be difficult to separate home and work when they’re happening in the same location. It’s important to set aside residency days as much as possible, even in your home environment. Be in a room with a door that closes. Put a sign on the door to remind family members and housemates that you’re at residency. Prep food ahead so you can be well-fueled.

Second, STRETCH! Make sure you’re moving around between events, moving locations when you can, turning off your camera to do some yoga. Just like on Campus, you have to pace yourself. Last residency, I ended up eating all my meals standing and walking around the house, just to make sure I got some movement in my day.

Third, find ways to connect that work for you. Some ideas: Introduce yourself on Discord before residency starts. Ask some questions of people who are ahead of you in the program. Take advantage of the small group workshops to get to know people. Come to events like Morning Coffee and Cafe Anna Lunch. Reach out to a GA by email or on Discord. And if you have ideas for student-led events or other ways to connect, reach out to the Cloud Coordinator.

Lastly, take care of yourself. Residency is intense, and layering the technology piece on top of the residency schedule can be a lot. Discover where your limits are, and don’t push past them. There are a few mandatory events (like workshops–don’t miss those!), but many things can become asynchronous. So take breaks when you need them, get outside every day, and stay hydrated!

To learn more about our WCYA program, check out our website.

To learn more about Anne-Marie, read about her at amstrohman.com.

I grew up in rural West Virginia and went to undergrad thinking I was going to be an English literature professor who wrote creatively on the side. That still makes me laugh, thinking I’d have so much free time as a professor. Anyway, to make a very long and roundabout story shorter, while pursuing an MA in English literature, I finally admitted that what I really wanted–what I’d always secretly wanted–was for creative writing to be my main focus. I started attending writing conferences, discovered a love for YA fiction, and after my day job, I’d work on a novel. I’d only ever written really short creative pieces before, so when I proved to myself that I could do it—I could write an entire book—I decided that I was going to learn to do it well. That led to my applying to VCFA (shout out to my fellow Summer 2012 Secret Gardeners!). Since graduating, I’ve become a published author, a writing instructor, and a parent of three kids, the first of whom was born two months before my VCFA graduation! I’m a passionate advocate for normalizing mental health care, debunking the stereotypes surrounding rural people, and protecting the earth.

I grew up in rural West Virginia and went to undergrad thinking I was going to be an English literature professor who wrote creatively on the side. That still makes me laugh, thinking I’d have so much free time as a professor. Anyway, to make a very long and roundabout story shorter, while pursuing an MA in English literature, I finally admitted that what I really wanted–what I’d always secretly wanted–was for creative writing to be my main focus. I started attending writing conferences, discovered a love for YA fiction, and after my day job, I’d work on a novel. I’d only ever written really short creative pieces before, so when I proved to myself that I could do it—I could write an entire book—I decided that I was going to learn to do it well. That led to my applying to VCFA (shout out to my fellow Summer 2012 Secret Gardeners!). Since graduating, I’ve become a published author, a writing instructor, and a parent of three kids, the first of whom was born two months before my VCFA graduation! I’m a passionate advocate for normalizing mental health care, debunking the stereotypes surrounding rural people, and protecting the earth.

Wild Things: There have been some incredible and nerve-wracking advancements in the realm of Artificial Intelligence as of late. You deal with this subject in your upcoming book Future Tense. Can you tell us a little about your new book and what you researched in writing it?

Wild Things: There have been some incredible and nerve-wracking advancements in the realm of Artificial Intelligence as of late. You deal with this subject in your upcoming book Future Tense. Can you tell us a little about your new book and what you researched in writing it? MB: Right now, ChatGPT writes terrible endings. It’s the biggest tell. Everybody learns from each other and makes peace at the end. It’s a fever dream of the centrist mainstream media, but in story form. So there’s that. ChatGPT also can’t track narrative threads for the duration of a novel—yet. (It got much better during the time I conducted my research, from something laughably kooky to merely irritatingly unimaginative).

MB: Right now, ChatGPT writes terrible endings. It’s the biggest tell. Everybody learns from each other and makes peace at the end. It’s a fever dream of the centrist mainstream media, but in story form. So there’s that. ChatGPT also can’t track narrative threads for the duration of a novel—yet. (It got much better during the time I conducted my research, from something laughably kooky to merely irritatingly unimaginative).

4. Tell us a bit about you. What makes you tick as an author?

4. Tell us a bit about you. What makes you tick as an author?

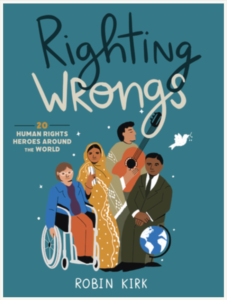

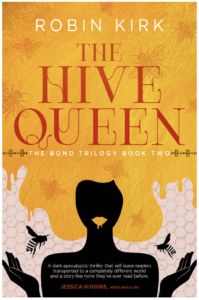

In my life, I’ve written in virtually every format: essays, op-eds, poems, fiction (novels, novellas, short stories, and flash fiction), press releases, technical reports, etc. I even drafted an opera based on my neighborhood list serve! For me, format is a choice that leads to the audience you are seeking as a writer and what effect you hope to have. But in all of these formats, my theme is very much the same: justice. In Righting Wrongs, I wanted to highlight that rights are envisioned, then won, then defended. Human rights were always something people had to think up, then work to achieve. I want kids to know about the people who did that on women’s rights, the laws of war, animal rights, and much more. In The Bond Trilogy, I use story to explore how rights work in an alternate world. My heroine, Dinitra, is raised to believe that men are inherently violent and should be eliminated. That’s one of the real-world ways of thinking that leads to genocide. In the course of the series, Dinitra comes to question everything, even the idea that animals and mutants—mixtures of animal and plant—don’t have rights equal to hers. The main character in The Mother’s Wheel is a mutant, Sil, who ends up saving her and creating a found family that is just as loving and intertwined as any purely human one.

In my life, I’ve written in virtually every format: essays, op-eds, poems, fiction (novels, novellas, short stories, and flash fiction), press releases, technical reports, etc. I even drafted an opera based on my neighborhood list serve! For me, format is a choice that leads to the audience you are seeking as a writer and what effect you hope to have. But in all of these formats, my theme is very much the same: justice. In Righting Wrongs, I wanted to highlight that rights are envisioned, then won, then defended. Human rights were always something people had to think up, then work to achieve. I want kids to know about the people who did that on women’s rights, the laws of war, animal rights, and much more. In The Bond Trilogy, I use story to explore how rights work in an alternate world. My heroine, Dinitra, is raised to believe that men are inherently violent and should be eliminated. That’s one of the real-world ways of thinking that leads to genocide. In the course of the series, Dinitra comes to question everything, even the idea that animals and mutants—mixtures of animal and plant—don’t have rights equal to hers. The main character in The Mother’s Wheel is a mutant, Sil, who ends up saving her and creating a found family that is just as loving and intertwined as any purely human one. I had just finished the draft of an adult novel and was pretty sad. I was on vacation with my family and ended up walking down a mountain largely by myself (everyone was ahead of me). I’d just finished The Book Thief by Markus Zusak and was so impressed by how he tackled the incredibly difficult theme of humanity in the midst of the Holocaust. Doubly impressive that he did this with kid readers in mind. I wanted to do something in the same spirit in a fantasy world. So I thought, ‘What group of people would most of us say has damaged the world the most – and who many would then believe should be controlled or even eliminated?’ The answer was easy: men. And that’s the seed of The Bond, where Dinitra has been taught that it’s not only natural to confine men. Getting rid of them entirely is the best and most ethical way to protect the world. What I learned is EVERYTHING. This early draft was what I sent as part of my application to VCFA. Looking back, it was TERRIBLE from start to finish and in every way. But it became the template that helped make me a better writer, good enough, at least, to turn this idea into a publishable book.

I had just finished the draft of an adult novel and was pretty sad. I was on vacation with my family and ended up walking down a mountain largely by myself (everyone was ahead of me). I’d just finished The Book Thief by Markus Zusak and was so impressed by how he tackled the incredibly difficult theme of humanity in the midst of the Holocaust. Doubly impressive that he did this with kid readers in mind. I wanted to do something in the same spirit in a fantasy world. So I thought, ‘What group of people would most of us say has damaged the world the most – and who many would then believe should be controlled or even eliminated?’ The answer was easy: men. And that’s the seed of The Bond, where Dinitra has been taught that it’s not only natural to confine men. Getting rid of them entirely is the best and most ethical way to protect the world. What I learned is EVERYTHING. This early draft was what I sent as part of my application to VCFA. Looking back, it was TERRIBLE from start to finish and in every way. But it became the template that helped make me a better writer, good enough, at least, to turn this idea into a publishable book. The idea was very much born in the classroom. I teach human rights to undergraduates. Again and again, I understood that they thought of human rights as something everyone got, kind of like a driver’s license, and that was consistent through time. This is in part a huge failure of the US educational system, but it goes further than that. My students simply couldn’t see that real people were behind the rights they took for granted. And real people are also constantly pushing at the boundaries of ideas of rights to include more people—women, children, LGBTQIA+, the disabled, even animals. I wrote this book not only to highlight the very real people behind human rights, but also show them, these new generations, that human rights now belongs to them and they get to continue to expand these ideas.

The idea was very much born in the classroom. I teach human rights to undergraduates. Again and again, I understood that they thought of human rights as something everyone got, kind of like a driver’s license, and that was consistent through time. This is in part a huge failure of the US educational system, but it goes further than that. My students simply couldn’t see that real people were behind the rights they took for granted. And real people are also constantly pushing at the boundaries of ideas of rights to include more people—women, children, LGBTQIA+, the disabled, even animals. I wrote this book not only to highlight the very real people behind human rights, but also show them, these new generations, that human rights now belongs to them and they get to continue to expand these ideas. When I finished the first draft of The Bond, I thought that was it, that I was done with these characters and this world. But my son, about 10 at the time, said to me, “Boys love series. They want to know what they’re getting into. You should write a series.” I immediately dismissed this. Then gradually, I started to see how rich this world could be. The Hive Queen was terrifying to write but also so satisfying. I’d completed The Mother’s Wheel when the original published canceled the contract (in the midst of COVID). So I was faced with a choice–leave the story as is or find a way to complete the trilogy? I realized that I couldn’t leave the story behind; I needed to finish. Otherwise, I realized, this world, these beloved characters, would be no more. I HAD to finish.

When I finished the first draft of The Bond, I thought that was it, that I was done with these characters and this world. But my son, about 10 at the time, said to me, “Boys love series. They want to know what they’re getting into. You should write a series.” I immediately dismissed this. Then gradually, I started to see how rich this world could be. The Hive Queen was terrifying to write but also so satisfying. I’d completed The Mother’s Wheel when the original published canceled the contract (in the midst of COVID). So I was faced with a choice–leave the story as is or find a way to complete the trilogy? I realized that I couldn’t leave the story behind; I needed to finish. Otherwise, I realized, this world, these beloved characters, would be no more. I HAD to finish. If I had to choose one, I’d say Judith Heumann, a champion of disability rights. At the time the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was agreed to in 1948, there was no recognition at all of the rights of the disabled. This is despite the fact that the person who chaired the effort, Eleanor Roosevelt, had lived with a disabled person, her husband, President Franklin D. Roosevelt (he died on an unrelated cause in 1945). Like FDR, Heumann contracted polio. She began to use a wheelchair as a young girl. At seemingly every turn, she was faced with discrimination. Instead of giving up, she and other disabled activists fought back, often very creatively. It’s largely due to their persistence that we have many accessible buildings, close-captioning, accommodations in the classroom and work, elevators, and so, so much more. Heumann is constantly reminding people that we all face potential disability because of life, especially as we age. Acknowledging and defending the rights of the disabled is good for us all.

If I had to choose one, I’d say Judith Heumann, a champion of disability rights. At the time the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was agreed to in 1948, there was no recognition at all of the rights of the disabled. This is despite the fact that the person who chaired the effort, Eleanor Roosevelt, had lived with a disabled person, her husband, President Franklin D. Roosevelt (he died on an unrelated cause in 1945). Like FDR, Heumann contracted polio. She began to use a wheelchair as a young girl. At seemingly every turn, she was faced with discrimination. Instead of giving up, she and other disabled activists fought back, often very creatively. It’s largely due to their persistence that we have many accessible buildings, close-captioning, accommodations in the classroom and work, elevators, and so, so much more. Heumann is constantly reminding people that we all face potential disability because of life, especially as we age. Acknowledging and defending the rights of the disabled is good for us all.